A timegrapher is an essential electronic device for measuring the accuracy of a mechanical watch. It works by using a sensitive microphone to record a watch’s beat, which is then displayed on a small LCD screen. To use it, you mount your watch on a stand connected to the microphone. Below, you can see the display and the stand that holds your mechanical watches.

If you’re buying a used watch or simply want to check the health of your timepieces, the first three readings on a timegrapher are the most critical: rate error, amplitude, and beat error. I will discuss the fourth reading later.

Understanding the Key Readings

1. Rate Error

This value tells you how many seconds per day your watch either loses (-) or gains (+). Ideally, you want a reading of 0, though even COSC-certified watches allow for a deviation between -4 and +6 seconds per day (measured over ten days). If your watch loses more than four seconds per day, it can usually be manually adjusted via the balance wheel—unless the issue is related to low amplitude, which is another matter entirely.

2. Amplitude

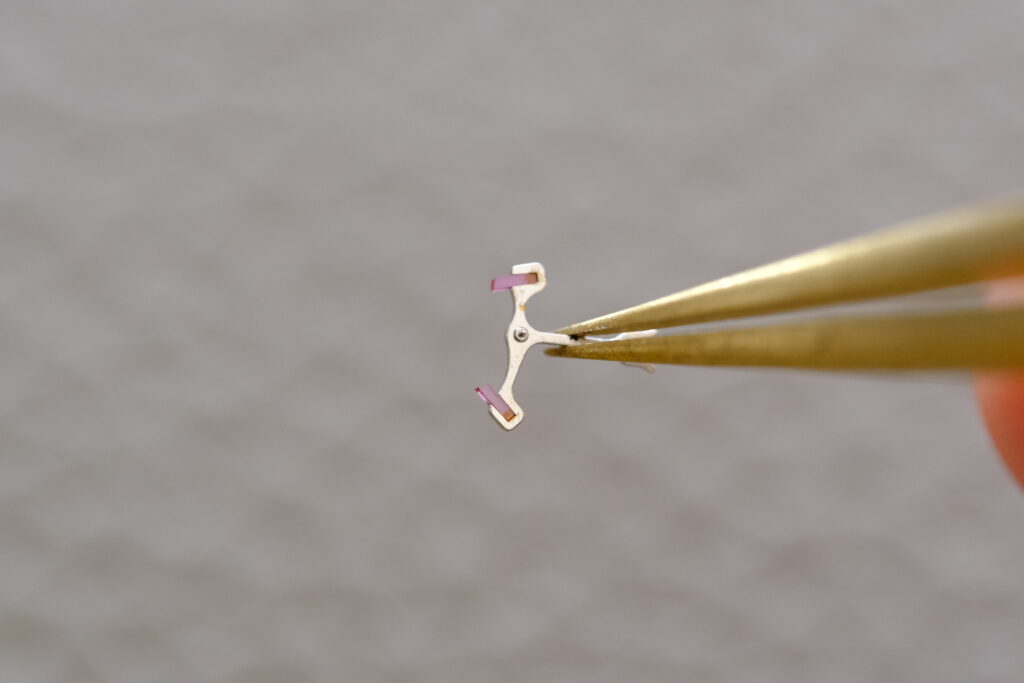

Amplitude measures, in degrees, the total distance the balance wheel moves in both directions. The goal is to maintain a healthy amplitude, as it indicates efficient energy transmission through the movement. Below, you can see which part of a mechanical watch is called the balance wheel (photo on the left).

- If the amplitude is below 200, your watch likely needs lubrication, has friction issues preventing free movement, or has a problem in the gear train restricting power to the escapement. In this case, a service by a skilled watchmaker is recommended.

- If the amplitude is above 315, it may indicate excessive lubrication, which can damage the pallet fork over time (photo on the right).

- Amplitude tends to be higher when the watch is dial-up or dial-down and decreases when placed in a vertical position due to increased friction in the movement.

3. Beat Error

The beat error measures the time difference in how long the balance wheel swings in one direction versus the other. Ideally, the reading should be 0, but some watches are regulated to maintain a low beat error across multiple positions, while others are adjusted for just one position (usually dial-up). If your timegrapher shows a high beat error, a watchmaker can usually adjust the balance wheel to correct it.

It’s important to note that all three readings may vary based on the watch’s position—what you see with the dial-up may differ significantly from vertical or dial-down positions.

You may also be wondering about the dots below the measurements on the Timegrapher display. These dots visually represent the beat error. If the beat error is 0, you will see a single line. However, if the microphone detects an error of a few milliseconds, the display will show two lines, with the gap between them representing the magnitude of the error. The larger the beat error, the wider the gap between the lines.

The Fourth Reading: Lift Angle & Beat Rate

The fourth reading displays two values:

- Lift Angle: This is typically 52 degrees for most modern watches. If needed, you can manually adjust it on the Timegrapher to ensure more precise readings.

- Beat Rate: This refers to the number of vibrations per hour of your movement.

If you know the specific lift angle of your mechanical watch, setting it correctly on the Timegrapher ensures more accurate results.

When Should Your Watch Be Serviced?

If your timegrapher consistently shows low amplitude in all positions or dramatically off readings in just one position, it’s time for a service. Also, always measure your watches when they are fully wound, as a partially wound mainspring delivers less power, leading to lower beat rates.

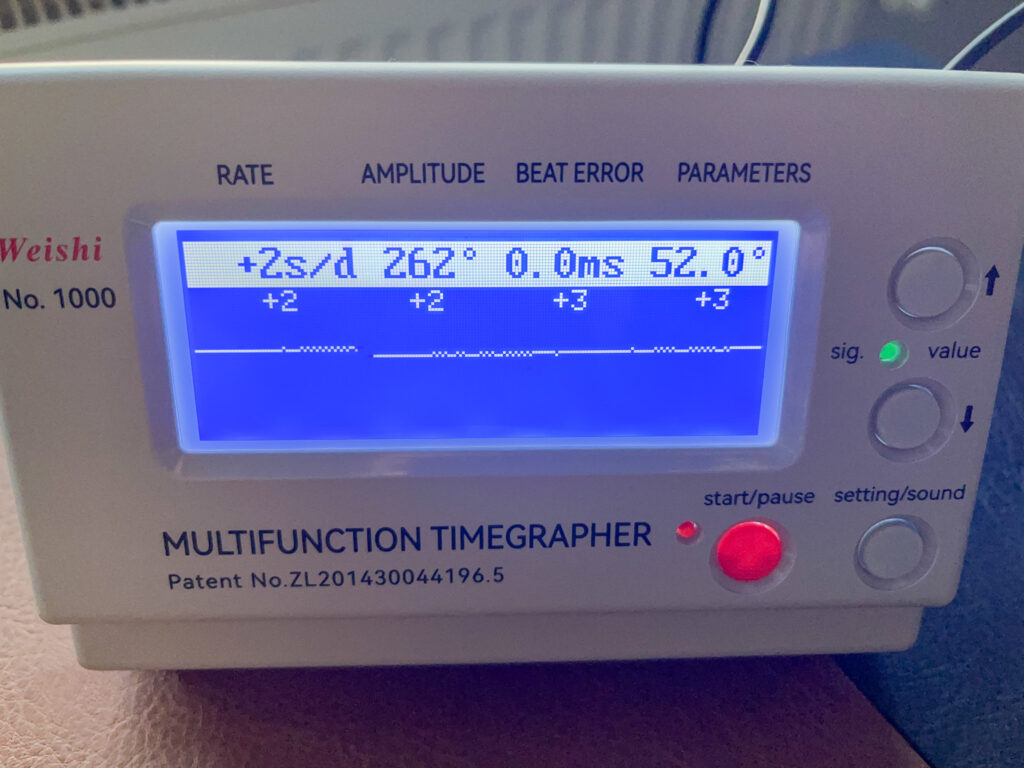

My Watch Readings

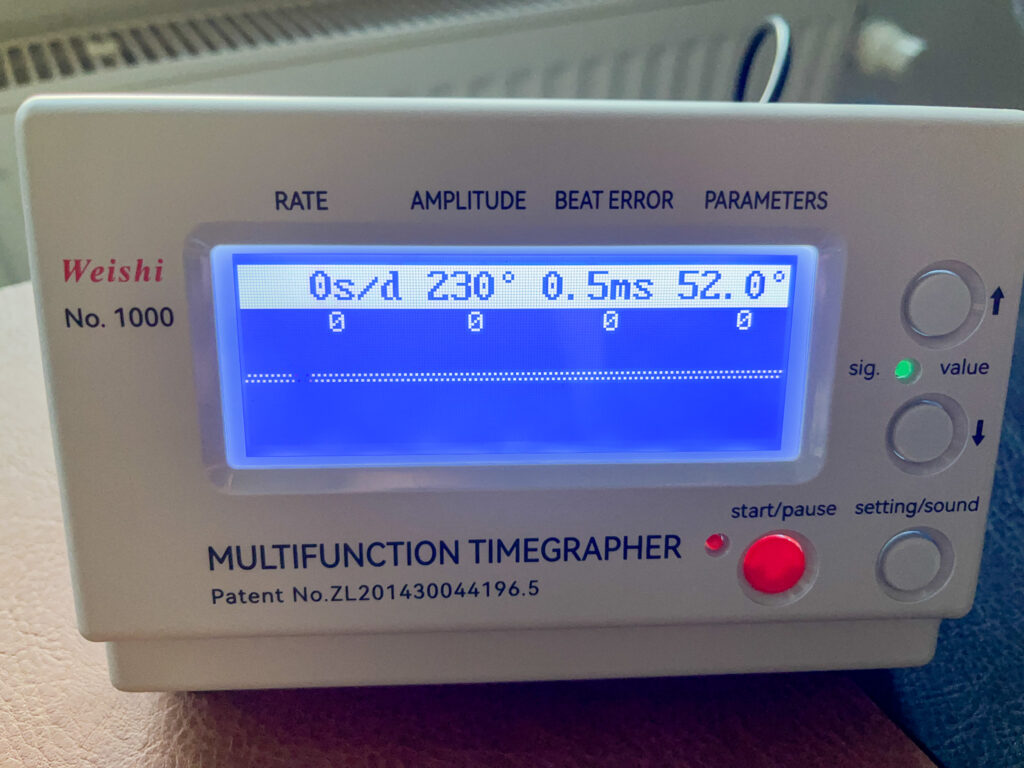

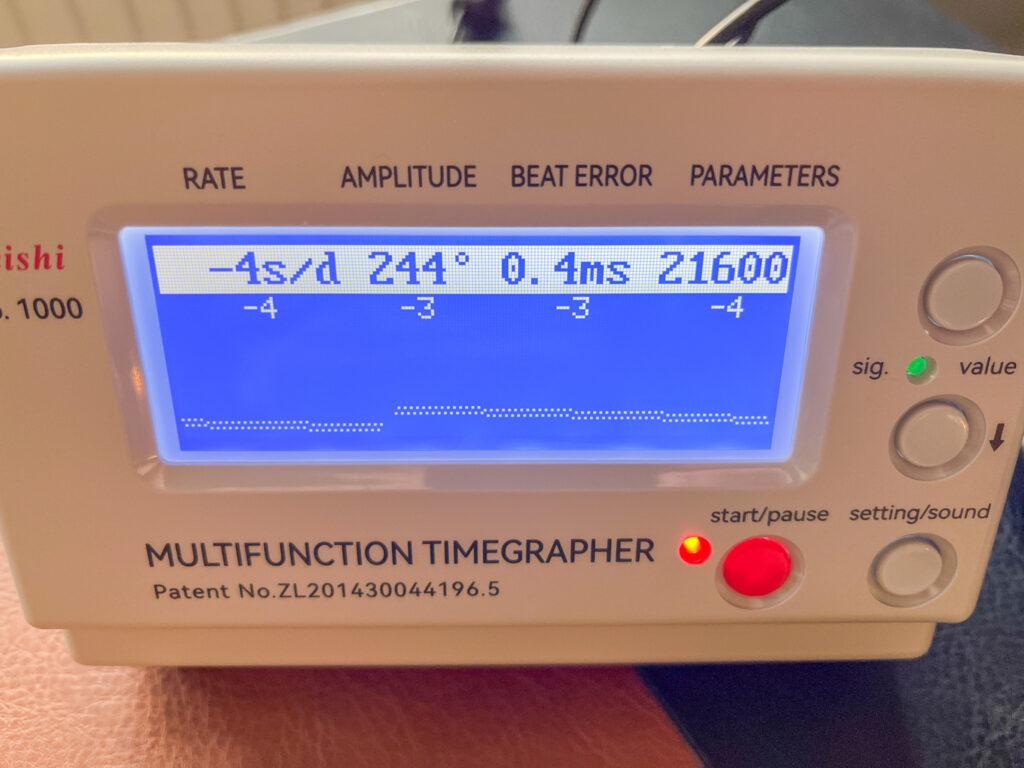

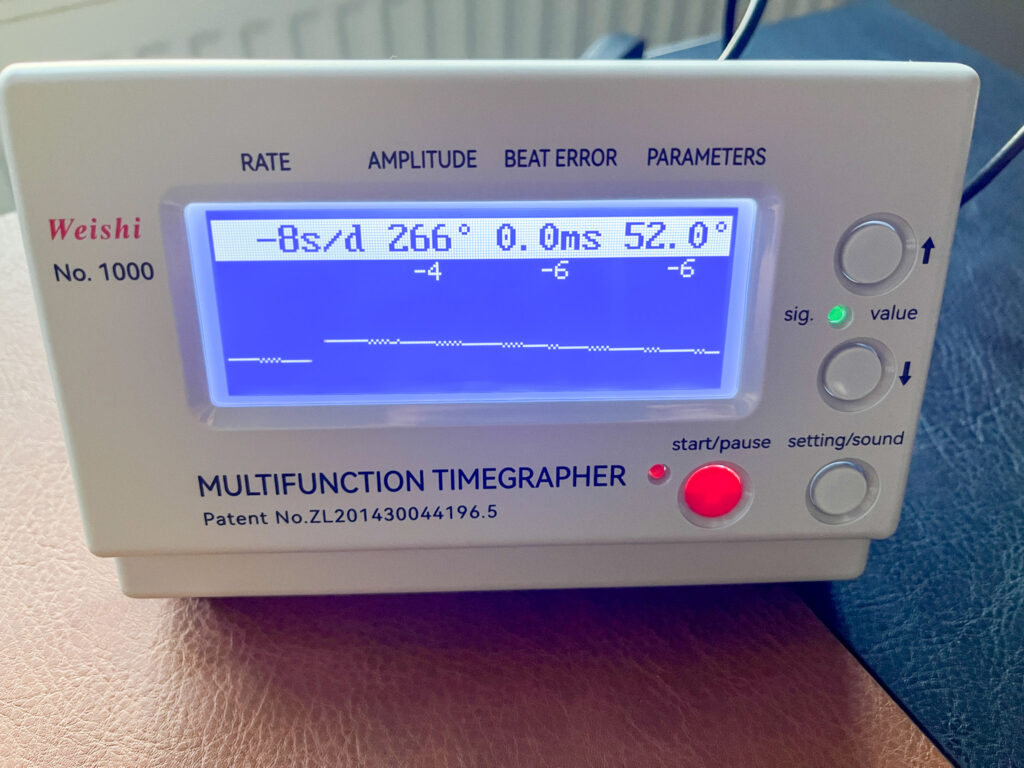

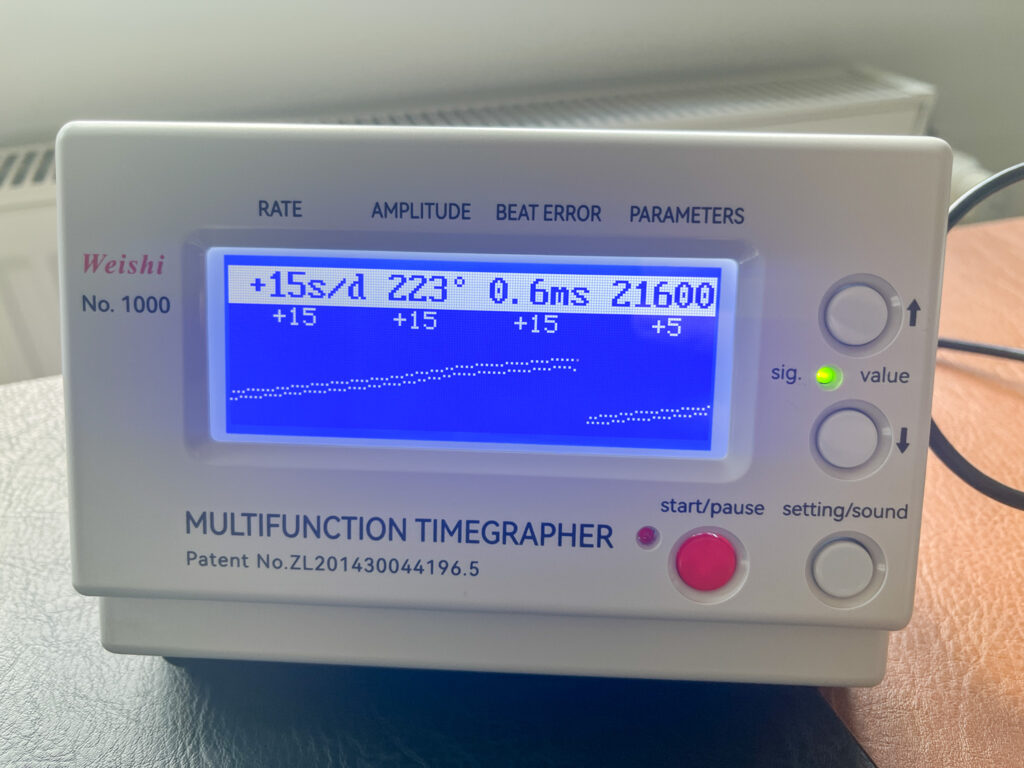

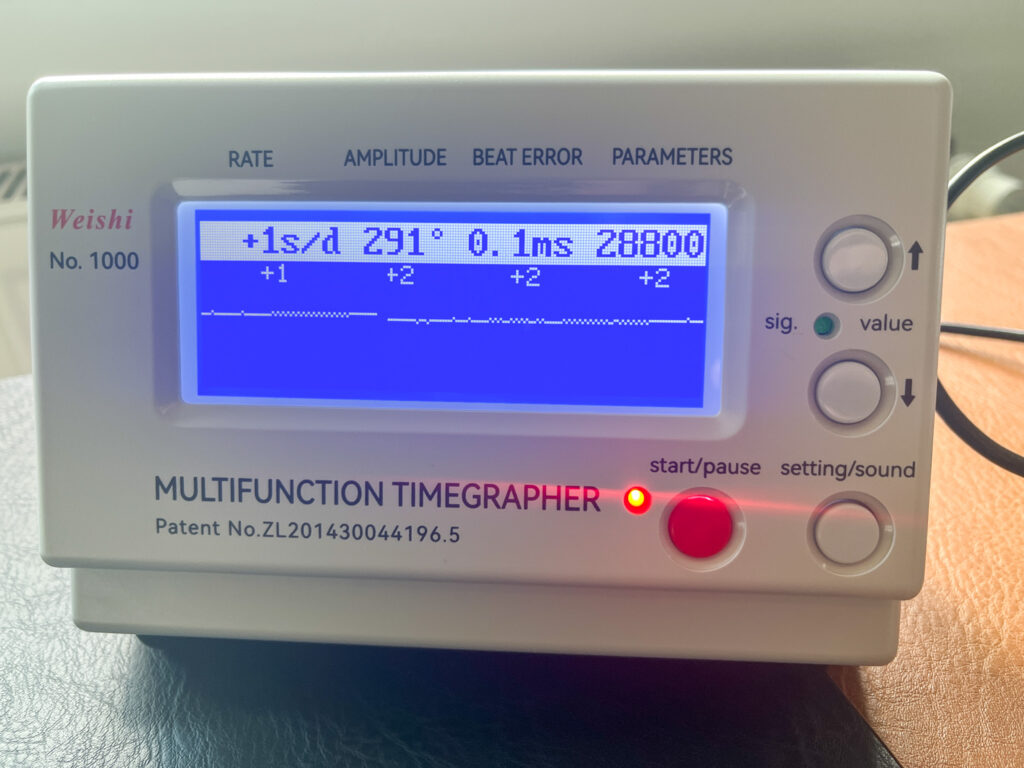

You might be wondering how my own watches performed. To my surprise, my Tudor showed relatively low amplitude—around 270. I expected closer to 300, but after researching, I discovered that many Tudor and Rolex watches naturally exhibit lower amplitude. As I don’t yet own a Rolex, I can’t confirm this personally, but for now, I’ll take the watch blog’s word for it. Fortunately, the rate error and beat error were low. Below, you can see the measurements of the Black Bay 54 in both dial-up and vertical positions. The watch is one year old, and I believe the mainspring was fully or almost fully wound at the time of measurement. Remember what I said here. It will age poorly.

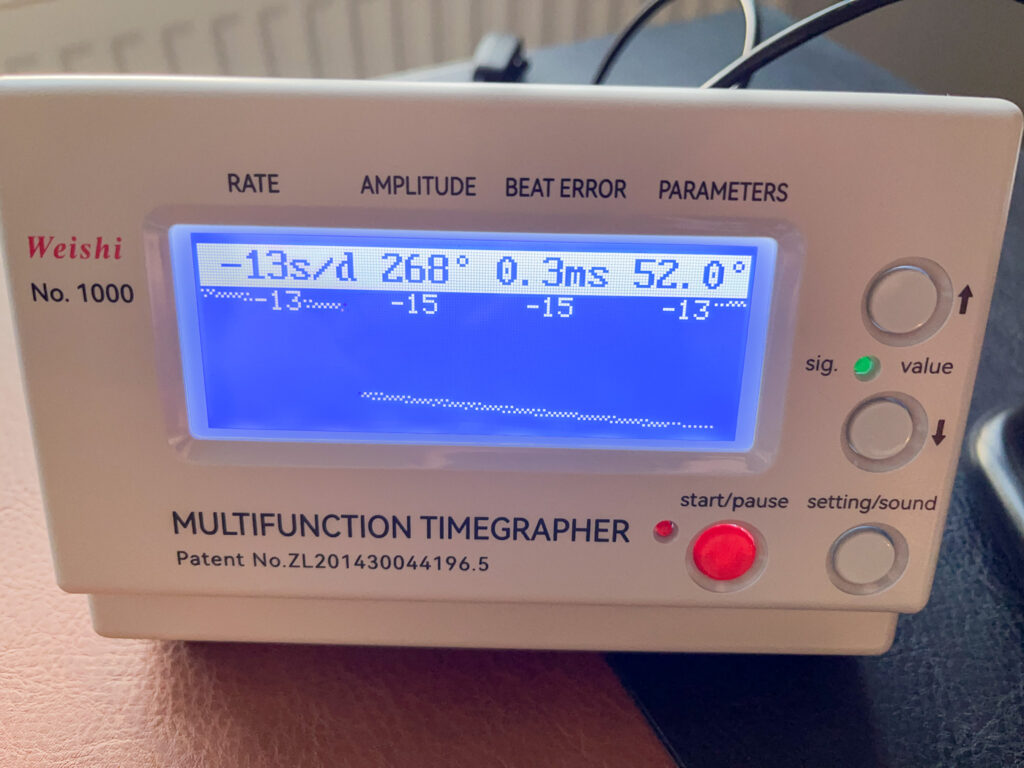

My Seiko results were less surprising. For its price point, it performed admirably, though the beat rate in the vertical position could be improved. This highlights why some watches cost more than others—Seiko didn’t regulate the movement in all positions. That said, its amplitude was good, and the beat error was acceptable.

Then, there’s my first mechanical watch—the Roamer. If you’re new to my site, you may not know that the crown once broke off. One day, I took it out of my watch box, pulled the crown to set the time, and ended up holding it in my hand. Let’s just say my chest tightened at that moment. I took it to the shop where my wife had purchased it, and while they replaced the crown, they also managed to scratch the caseback. Thanks to my new macro lens, I can now see they didn’t even clean the see-through caseback before reassembling it.

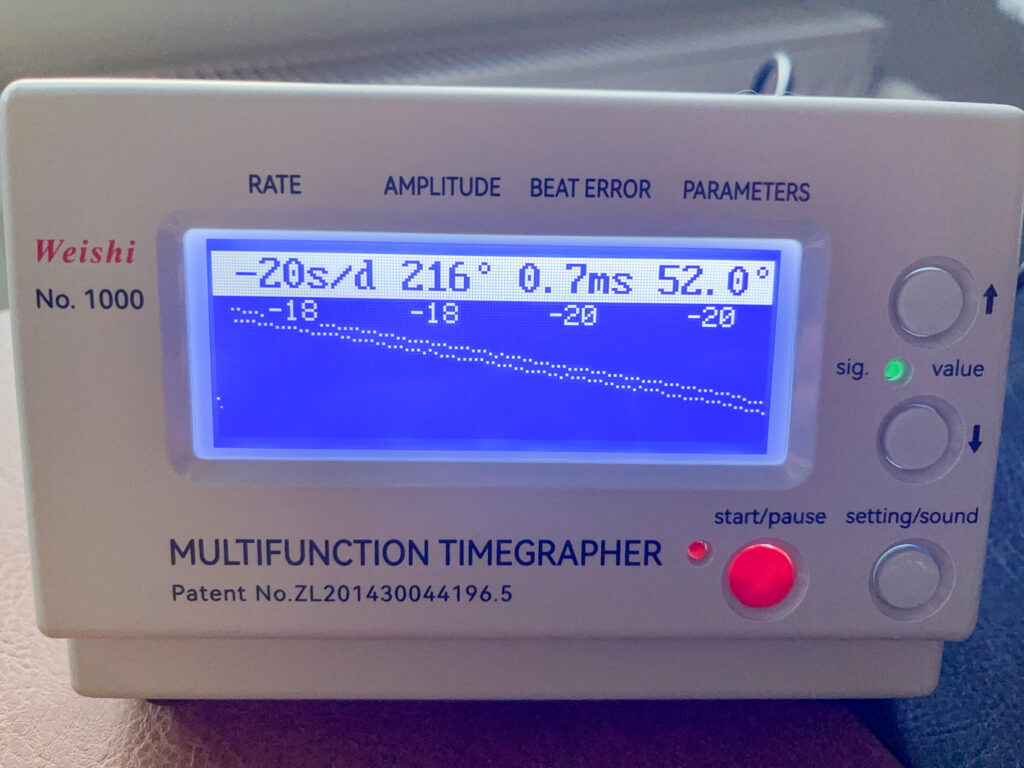

The rate error suggests my Roamer needs adjustment, but fortunately, I haven’t noticed significant time loss when worn continuously. Surprisingly, it has the highest amplitude among all my watches in both positions.

What about my wife’s mechanical watch? She also has a wonderful Seiko. Moreover, she wears her timekeeper daily, whereas I change my watches throughout the week (some weeks more than others). Let’s see.

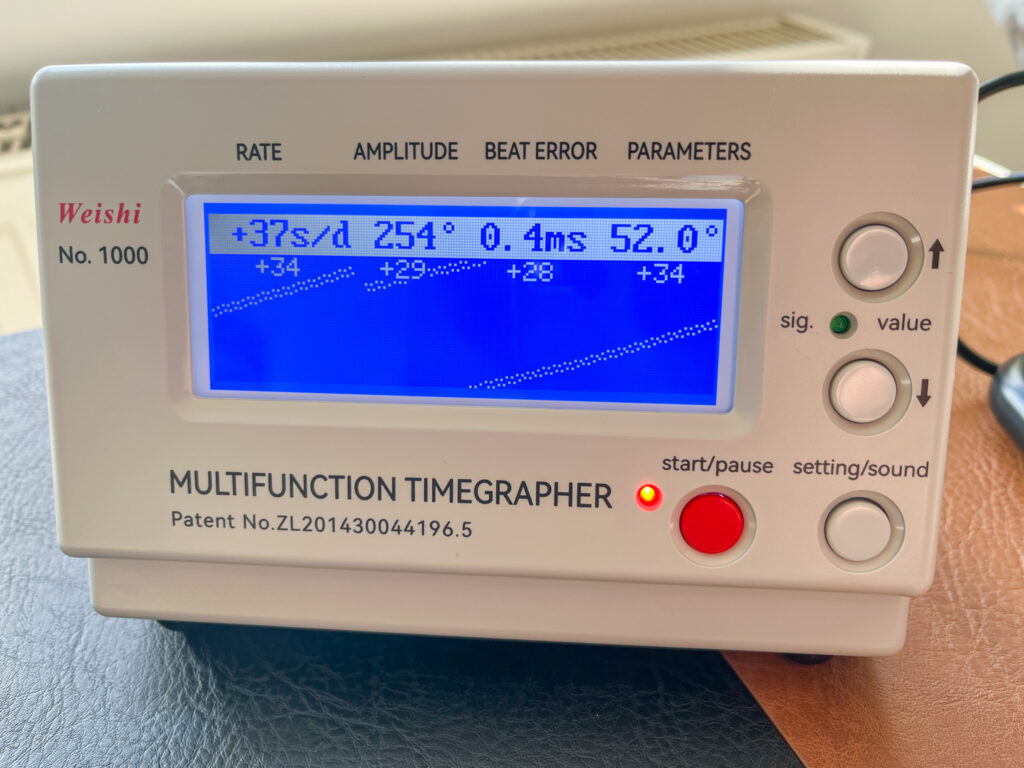

These were unexpected readings. In both positions, this Seiko gains time. When the dial is up, it gains more than half a second per day, which clearly indicates that this movement needs adjusting. Moreover, this observation is reinforced by the reading with the dial in a vertical position, where it gains approximately 15 seconds per day. The beat error and amplitude are within an acceptable range. However, while monitoring the Timegrapher readings, I noticed fluctuations in the vertical position—both the amplitude and beat rate fluctuated significantly, jumping from +15 seconds to 0 seconds and back to over 10 seconds. At one point, I even observed the amplitude dipping below 200 degrees. My best guess? This Seiko’s movement might not be properly lubricated—or perhaps it has excess lubrication.

This experience has sparked my curiosity. I now feel tempted to purchase a cheap mechanical Seiko and disassemble it. If I could successfully take it apart, clean, lubricate, and reassemble it, I might be encouraged to work on my own watches—though my Tudor will remain off-limits for now. Could this be a future article? Maybe even a chapter in my upcoming coffee table book?

One more thing…

I was wearing my Tudor today while photographing my wife’s watch. Out of curiosity, I decided to measure it.

To my surprise, the amplitude was close to 300 degrees. Remember what I mentioned earlier about Tudors and Rolexes? This gave me an idea—what if I measured each of my watches daily over a week? I could take the first measurement before putting it on, after winding if necessary, and a second measurement at night before placing it back in the watchbox. It’s an intriguing experiment—I’ll have to give it some thought.

Should You Buy a Timegrapher?

If you’re a watch enthusiast or collector, you might be wondering whether a timegrapher is worth the investment. I’ll save you the debate: Yes, you should get one. You can find this model for around 170 to 230 euros on Amazon.

For those with large collections, using a timegrapher can be both fascinating and slightly stressful. However, it’s a fantastic tool to determine when your watches need servicing. While manufacturers provide general guidelines on when to clean and lubricate their watches, unexpected issues can arise that warrant earlier maintenance.

Ultimately, beyond its practicality, using a timegrapher is simply a fun experience. And that’s what this hobby is all about.

I love this hobby.

Kindly,

Olaaf